Wovenhand is priming its audience.

The stage still empty, a recording of Native American flute drifts out from the speakers, followed by one of a pow-wow, origin unknown. A collection of red and white bandanas dangles from the mic stand, intertwined as if the image has a meaning we won’t learn about. An old-school mic sits on top. A dream catcher hangs from an amp a few feet back. Valley Bar is a dark and candlelit cave every night of the week, and tonight, it only serves the mood more. The details stack up to create the feeling that the place has been cleansed in preparation for The Big Show. David Eugene Edwards, the gothic stranger, the man we are all really here to see, Wovenhand’s frontman, owns the stage before you even walk in the door.

Twenty-somethings gather at the front and at the bar dressed in black from head to toe. A couple of punk rockers walk in wearing black t-shirts with their sleeves cut off. For all we know, Edwards is across the street getting a taco, but we’re here, studying his stage, being slowly immersed into his vision, exactly as he intends it.

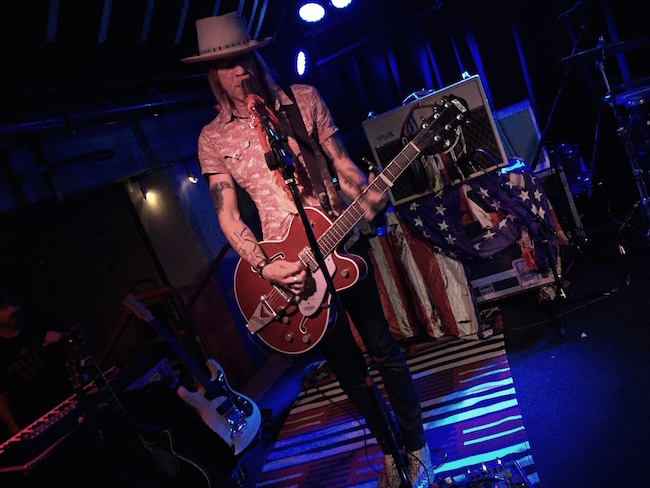

When he steps out, band members close behind, he says nothing. He straps on an old red Gretsch and the four-piece lights up a barrage of what might be described as folk-infused, dream-pop post-metal, as if the Deftones had moved to the Appalachians.

Edwards wears white snakeskin boots and a feathered cap. His face is chiseled and shadowy almost all of the time, as if it was carved out of jagged rocks and left in the desert sun to darken and weather. In sum, he conjures the image of an old Western conman preacher who crawls into town to charm the women, cast spells, and drink all the whiskey. But when his baritone voice bellows out, it’s all brimstone and piety.

Right away, Edwards is neck-deep inside something powerful. His eyes roll into his head, eyelids fluttering over the top, his head and arms jerking and twisting anytime they pull away from the mic and guitar. He raises his hand, folds his arms, holds his hand against his face. At any moment, he could start speaking in tongues. At times, away from the mic, his mouth still moving, it looks like he is. Other times, it’s indecipherable growls in Lakota.

He plays only old guitars. At one point, he straps on a banjola nearly as worn as Willie Nelson’s Trigger, but all the wear is on the upstroke, just above the sound hole. Below it, a pick guard keeps the abuse at bay. Gothic Americana, they call this music, but it’s grown heavier, screechier since Edwards first had that term attached to him. On the Valley Bar stage, it’s a menacing wall of sound that beats you in the chest for 45 straight minutes. Wovenhand has gotten more ominous over the years. Edwards has come a long way since the ostinato-centric, banjo-heavy days of his previous incarnation, the Denver-based 16 Horsepower.

Edwards says nothing to the audience between songs, but this isn’t personal. He’s in a deep place. A serious place. His intent is to live inside of it for as long as the guitars ring out.

Edwards is the Jim Morrison of religious songwriters. His faith comes out in the kind of ferocious poetry that kicks you backward with no sign of the sweetness of a lover’s ode. This man’s God is one who shoves his way out through Edwards’ bold voice, a snarling wall of guitars, relentless bass, and drums so stylish and hard-hitting to recall The Cult’s “Love” album, circa 1985. This man is no preacher. He’s one of the possessed, here to draw you in through the power of his own fever. To put his inner sinner on display and challenge everything you know about the Pentecostal ideology he grew up with and now uses for source material.

From the audience, a man called John Lies (pronounced “lease”) says to me, “He’s channeling God when he does this,” and, “He’s the Ian Curtis of our time” (Curtis being the suicided former singer of Joy Division, a man who also had a penchant for headiness and erratic body movements). Lies tells me I should talk to his friend, Artemis, who has followed Wovenhand to countless shows.

Artemis Balint confirms this, saying she’s seen the band “many” times. She references the fact that Edwards used to sit through his sets on a stool, and that it was a surprise to see the mic set up at a standing height. She suggests Edwards is “grumpier now,” but professes her devotion to the music, saying it’s “[…] very raw, it’s visceral, it’s post-apocalyptic.”

Whether Edwards is struggling, taking a stand, or something else, no one knows for sure, but his powerhouse approach has indisputable appeal to the broken kids. The damaged ones. The dark ones. If you were raised on sunshine and Christian rock, odds are you won’t find yourself in his audience. His art is for the conflicted. And it comes out as pure intensity.

Wovenhand’s tour manager Jim Norris has worked in the Denver music scene for the last 20 years and has known Edwards since the early days of 16 Horsepower. He cites that intensity as the reason for getting involved: “It’s like a spiritual experience. It’s beyond regular music. It’s unlike anything else that there is.” He’s seen enough to know on this stint alone. “I think I’ve done 22 shows so far this tour, and every night, it just gives you goose bumps.” He says, though, that he wouldn’t call it preaching. He thinks Edwards is working out his religious issues in a “more intense, William Blake kind of way — that battle between the good and evil. It’s beyond human comprehension.”

After the set, wrapping cords and turning knobs, the tasks of every stage musician, Edwards shakes several hands and smiles and is humble and thankful. But he stays quiet. And then he disappears offstage. Back to the life that gives him the fire he burns through note after note on stages all over the world.

Wovenhand is on tour with Chelsea Wolfe in support of its most recent album, Refractory Obdurate (2014). When this man’s fire leads him back to Phoenix for another night, don’t make the mistake of missing it.

Photos by Robert Hoekman, Jr.