Last month DPJ visited a downtown building undergoing renovation for its new tenants in Warehousing ASU’s School of Art: Part One. The second part of this story explores the warehouse’s history from the perspective of its owner, developer Michael Levine.

Over the past century, many of the warehouses of Phoenix have been either demolished or disappointingly modernized. All too often, they acquire a regrettable aura of Brutalism reflecting the utilitarian design of structures like Symphony Hall and its surrounding skyscrapers.

But a handful of these venerable buildings are slowly regaining their ageless appearance, re-emerging as majestic, enduring dowagers anchoring the architecture of downtown, thanks to preservationist-developer Michael Levine. “I’m very protective of the properties,” he says. “I try to look at the long-term effect and where they’re going to be in a hundred years.”

As a handful of graduate studios from Arizona State University’s School of Art prepare for the Third Friday opening reception on January 17 at Levine’s 605 East Grant Street warehouse, the School’s director, Adriene Jenik, is full of enthusiasm. “Our gallery and critique space will present greater opportunities to engage with [the public],” she says. Later, as Jenik describes the adaptive construction, she adds with a laugh, “It’s like an artist’s wet dream.”

Incoming Dean Tepper (courtesy Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts and Vanderbilt University / Steve Green)

The School of Art’s move comes as a new dean prepares to lead ASU’s Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts beginning July 1. Steven J. Tepper comes from positions at the Curb Center for Art, Enterprise, and Public Policy and Vanderbilt University, where his research and teaching focus on creativity in education and work as well as conflict over art and culture.

Graduate painting and drawing programs will move downtown with the Step Gallery, followed by sculpture, fibers, and intermedia, ultimately occupying 26,232 square feet including plenty of mouthwateringly spacious 250-square-foot individual studios. One large room, built in 1959, features a 15-ton A/C unit and seven studios with LED lighting and no ceilings, allowing vast expanses of natural sunshine through overhead windows.

“Spatially, it’s been really fascinating,” says landlord Levine. “Because the [warehouse] ceilings are so high and you have ten-foot-high [studio] walls, you feel like you’re three years old. For the artists…to stand back…they’ll have no claustrophobia — they’ll have all the light they’ll want.”

CCBG Architects and Kitchell [construction company] have been working at a rapid pace to accommodate ASU risk management concerns while maintaining historical integrity. “They overbuilt,” says Levine with some satisfaction as he surveys the gallery. “This is a building inside a building…so they don’t touch the existing building.” For example, in one area an interior glass wall simultaneously protects and reveals the beauty of restored brick. “Conceptually, for historic preservation, it’s the same outcome,” he says, adding with a laugh, “Everything has been like a really beautiful puzzle — I’m watching all the pieces nest together, but it’s not a 2-D puzzle…it’s like a weird 3-D puzzle.”

Levine, who fabricated a Batmobile and a steampunk balloon for his family in the warehouse, has found it somewhat painful to give up his own “dream” creative space to provide fire egress for the new ASU construction. ”It was like the worst seller’s remorse I’ve ever had, because this is the perfect studio,” he says with a sigh, still grinning. “Having two cranes is like having two employees…two employees I don’t have to talk to.” He’ll move Levine Machine into the oldest warehouse in Phoenix: the Seed & Feed building at 411 South Second Street, built in 1905 by Swedish immigrants.

His other renovation successes include The Duce (at 525 S. Central), Arizona Cotton (at 215 S. 13th St.), and Bentley Projects (at 215 E. Grant St.), along with the 2007 grand prize in the Arizona Governor’s Heritage Preservation Awards.

Levine attended art school himself, studying architecture and drafting. He moved to the Valley 23 years ago and established his AAARDVARk AARMAdILLO Corporation for design and construction. As he points out features of the warehouse, Levine’s boundless enthusiasm for industrial restoration is palpable.

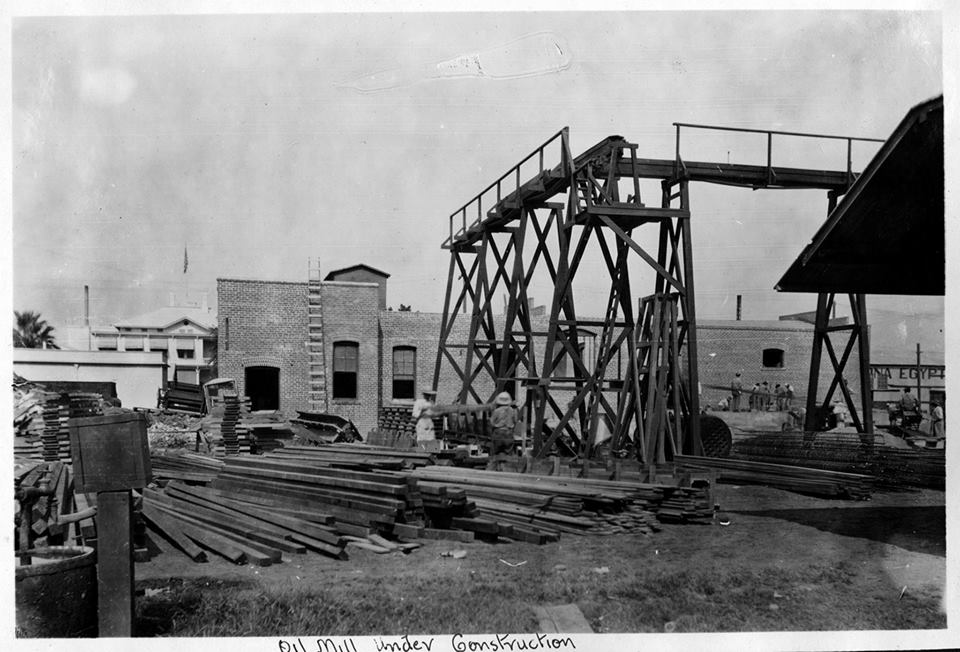

“This site’s really interesting,” he says, pointing toward the southwest area of the property. “The back corner…goes back to 1895 as the Phoenix Cotton Oil Company.” Levine gestures toward Grant, indicating original windows and concrete openings. “This corner building was built [around] 1909…this was McCall Cotton.” As Phoenix grew, so did the warehouse.

In 1917, as the United States began to prepare for war, a young vice-president of Goodyear Tire named Paul Litchfield came to the Valley. “With the power of the U.S. government and Goodyear Tire he buys…everything,” says Levine. “He buys every cotton field down here, he buys all the cotton gins, and he buys the entire ecosystem. Then they came and they built this two-story building…and as far as I can tell this was the headquarters for Goodyear.”

The warehouse operated under the subsidiary Southwest Cotton Company, Levine says. “The construction methodology that they used was board form and they had slits in the wall for the belts to go through and all the pulleys,” he describes. “And all that stuff is still there — all the slots are there, all the bolts. If you look at the very top you can still see the ghost [sign painted on the brick], and it says ‘Pure and uniform in quality,’ and on the left near the door it says ‘The best is the cheapest.’” He smiles and adds, “I try to leave all that history, all those scars.”

Levine learned that Andrew Karlson, an undocumented Norwegian immigrant and the first certified welder in Arizona, worked on the Roosevelt Dam before purchasing the warehouse in 1943, according to his granddaughter Mikelene Karlson. In tribute to the longtime owner of Karlson Machine Works, Levine hung a black-and-white photo of Karlson and his wife Marie on one of the structure’s restored brick interior walls.

“I had a Robin Hood mentality about saving these buildings,” Levine says, explaining his history of reinvesting in downtown warehouse preservation. “I’ve been holding on to these things against my own economic interest….” He continues, “The theme that runs through everything I do is…site-specific, so it’s all about…deconstructing and peeling things back.”

“I’ll try to do the restoration based off of the history, to find out what the character is,” Levine adds. “When you’re dealing with industrials…they’re living documents — they’re living buildings.”

He says matter-of-factly, “The greenest building is an existing building, and the best historic preservation is neglect, and that’s really what saved this building. Demolition’s easy to see, but historic equity disappearing by a thousand small cuts will still kill you.”

Learn more:

- ASU’s School of Art grand opening and open studios in downtown Phoenix

- Friday, January 17, 2014, 7 p.m.-9 p.m. (more information at ASU.edu)

- 605 E. Grant Street

- Michael Levine and Levine Machine, including past and ongoing warehouse projects

Update: An earlier version of this article referred to Michael Levine as an art teacher in Peoria, which is incorrect.