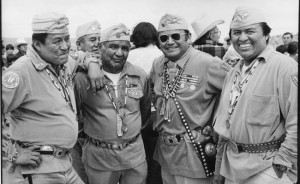

Code talkers Frank Thompson, Harold Foster Jr., William Dean Wilson and Teddy Draper in Window Rock, Arizona. Credit: Kenji Kawano, 1975

“I can tell you that because I came to the reservation it changed my life,” says photographer Kenji Kawano, “because I met a code talker when I was hitchhiking somewhere around 1975…Mr. Carl Nelson Gorman – he was one of the original 29. And also I met my wife.”

37 years later, the images from Kawano’s camera come to the Heard Museum this weekend as Navajo Code Talkers, an exhibit complemented by Native Words, Native Warriors from the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibit Service.

Born in Fukuoka, Japan in 1949, Kawano found that his imagination was fired by the work of photographers Robert Frank, W. Eugene Smith, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. After visiting American Air Force and Navy bases in Japan to take photos, he came to the United States following high school.

“My thinking was to take pictures in Los Angeles, make a portfolio, and take my work back to Tokyo to have a photography exhibit…and if I’m lucky, I might become a freelance photographer.” Kawano laughs. “But when I look back now, it was a terrible plan.”

“I told my parents, ‘I’m going to America, but only for three months,’” he continues, “but actually I went back to Japan 7½ years later with my Navajo wife.” Unable to find any good projects in Los Angeles, Kawano leaped at a friend’s suggestion that he explore Navajo culture.

“Since I grew up watching Western movies when I was small,” he recalls, “I thought, ‘Maybe that’s a good idea, to go to the reservation to take pictures of Native Americans in everyday life.’”

Although he spoke neither English nor Navajo, the 25-year-old Kawano ended up in the heart of the Navajo reservation, living with a family and working at a gas station in Ganado, where he learned both languages from customers.

Although he spoke neither English nor Navajo, the 25-year-old Kawano ended up in the heart of the Navajo reservation, living with a family and working at a gas station in Ganado, where he learned both languages from customers.

Kawano also broadened his experience by hitchhiking between Ganado, Window Rock, and Gallup. Along one of those roads he met Carl Gorman, and from then on Kawano’s life became inextricably entwined with the story of the Navajo code talkers.

Gorman was one of the first 29 Navajo men recruited by the Marines in 1942 to create a secret code based on the Navajo language. The code used Navajo words to indicate letters of the alphabet (for example: lha-cha-eh for “dog,” indicating the letter D) or certain military terms (lo-tso for “whale,” which meant “battleship”) – an ironic use of a Native American language the U.S. government tried diligently to eradicate in boarding schools.

Throughout World War II, the code remained unbroken by the Japanese, and around 420 Navajo code talker Marines served in the Pacific, communicating messages by telephone and radio. Occasionally, the young code talkers would be mistaken for Japanese and captured by fellow American soldiers. President Ronald Reagan designated August 14 as National Code Talkers Day, and in 2000 they were awarded Congressional Medals.

The man Kawano refers to as “my Navajo father,” Carl Gorman, helped create the code. He returned from the war, attended art school on the G.I. Bill, and eventually founded the Native American Studies Program at the University of California, Davis, befriending a young Japanese photographer along the way.

Navajo code talkers Private First Class Preston Toledo (left) and his cousin Private First Class Frank Toledo, 1943. Courtesy U.S. Marine Corps.

“Back in 1982, when Mr. Gorman was president of the Code Talkers Association, they chose me as official photographer and honorary member,” says Kawano, whose father served in the Japanese navy. He continues, “People say, ‘Why do you choose a former enemy?’ but Mr. Gorman said, ‘Kenji, we don’t hate you, because war is between two countries, not me and your father.’ So, quickly I became a friend of all the code talkers.”

After meeting his wife, Ruth Williams, at the College of Ganado, Kawano became the official photographer for the Navajo Nation and staff photographer for Navajo Times Today. In 1990 he published the book Warriors: Navajo Code Talkers, which contained a series of portraits.

“I really wanted people to know what young Navajo G.I.s did for this country – they didn’t use rifles; they used their language as a weapon,” explains Kawano. He’s delighted that his exhibition at the Heard will be displayed in tandem with Native Words, Native Warriors, which gives a great deal of background and context to the history of American Indian soldiers.

Kawano’s exhibition at the Heard features an array of snapshots taken between 1975 and 2012 and two portraits, including one young man holding a photo of his grandfather…who was photographed holding a photo of that same grandson as an infant. “I’m still taking pictures,” says Kawano. “I spend so much time for my project, and it never ends. This code talkers work is my lifework.”

- Both exhibits, Navajo Code Talkers and Native Words, Native Warriors, are on display at the Heard Museum through March 31, 2013.

- Find photographer Kenji Kawano’s portfolio and books on his website.

- The National Museum of the American Indian provides a companion website for the traveling Smithsonian exhibition Native Words, Native Warriors.

- Visit the Official Website of the Navajo Code Talkers, or find more information and documents on the National Archives website and the Naval History & Heritage Command website.

- The Navajo Code Talkers’ dictionary was declassified in 1968.

- Related articles in The New York Times include information about the Navajo code talkers and an obituary for Carl Gorman.