Paul Mosier has in his downtown Phoenix home boxes of handwritten journals going back to 1986. They’re filled with daily plans, scenes observed in coffee shops, notes about characters and stories he’s either invented or is about to invent, notes about his workday, his family, his morning. And he’s picky about them, the journals. He doesn’t like them to come with ruled lines. He doesn’t like the pages to be bright white. These journals get filled up by way of a near-constant scratching of pen on paper. No matter the events of the day, he’s effectively writing his way through it.

I should mention, Paul is a writer.

He’s the kind who doesn’t believe much in talking about writing, though. “I’m always suspicious about the usefulness of thinking about writing,” he says. “It’s not as fun as the actual writing.”

When he does talk, it’s about nearly anything and everything somehow relevant to the topic at hand. It’s without reservation. It’s without shame, without inhibition. If he feels it, thinks it, remembers it, imagines it, he’s likely to spill it out in a fast riff full of humor and analogies.

He says someone once compared his verbal stream-of-consciousness to a John Coltrane sax solo (a fact Paul approves of, by the way, because he happens to very much like John Coltrane). Legend has it, Coltrane said he never knew how to end a solo, to which someone suggested he try taking the saxophone out of his mouth.

Paul’s riffs frequently start in one place and go quickly to another, dancing their way into stories of his transgressive youth, stories of love, stories of his characters. The common object here being stories. He’s brimming with them, and they come out unfiltered regardless of who’s on the other side of the coffee shop table. By day, he is a green investments consultant, and his clients are just as likely as anyone else to hear about a drug-fueled college escapade, or a night of drinking far too much (something he stopped entirely a number of years ago). With any luck, it’s good for business.

Through the years, he has learned to match his vocal machinations note for note on paper. When you read his work, it’s easy to hear Paul inside of it. His voice floods every paragraph. This is the wish of most writers, to sound distinctly themselves. To put on the page the best rendition of what is already in their minds, whether they know it or not. To let their fingers do the typing and have the words come out true to their personalities, their voices.

He has done this. Paul’s written voice is his whole voice. To read him is to hear him.

He achieves this, he says, by handing himself off to the muse — whatever that thing is that puts ideas into your head and helps you form each sentence from the one before it. “I’m always kissing the muse’s ass,” he says, “because I really believe in it and I find it really interesting — the mystery of giving birth to a story.” He believes in it, listens closely to it. “I think the way that I work best is to just dutifully record what is being shown to me by the muse and then make sense of it later.” He does this to the point of self-deprecation about his involvement in the writing. He says he doesn’t create his stories so much as hear the ideas and get them down, whatever they are. “I can’t feel like I’m really responsible or that I can take credit for it,” he says. “I’m just trying to be a hardworking — you know, a good worker bee.” His job, as he describes it, is to “display what’s being screened in the film room inside my head.”

During the interview, he even reads me a short, innuendo-laden piece about the idea, wherein Calliope, the Greek muse of eloquence and poetry, is a woman in a bar who he overhears talking about him. “‘It’s so easy,’ she says. ‘I just show up and he’s ready to go.’” Then she says, “I don’t even have to buy him drinks.” He then goes home, opens his laptop, and waits for her to arrive.

She’s shown up more than once.

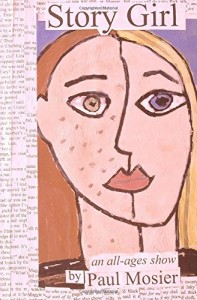

Paul has self-published two novels, one called “Story Girl” (for middle-grade kids), the other called “Breakfast at Tuli’s” (whose very first sentence marks it as decidedly not for kids). Both, however, were met by a solid round of rejection letters, every writer’s cross to bear.

Then he penned a third — another middle-grade book called “Train I Ride.” Without much hope for literary success, he thought it deserved “a decent burial.” He sent it out to agents anyway — a shorter list than before, indignant about having previously submitted to agents whose work he didn’t respect.

This time, one grabbed on. And once those details were sorted, it took just two weeks for two of the big five publishing houses (the book had been sent to four) to express wholehearted interest.

One of them, Harper Collins, made a preemptive offer — that is to say, an offer significant enough to avoid sending the book to auction and result in a bidding war. This happens when two houses go after the same book.

Paul liked the offer. The offer was good.

In addition to buying “Train I Ride,” Harper Collins offered Paul a second book with an option for a third. “I still feel like I’m living a dream,” he says.

The publishing process is no easy thing, no short thing. “Train I Ride” isn’t expected to hit shelves and Kindles until early 2017.

The wait, I expect, will involve more than a few journals. A whole lot of stories. Probably his next novel.

He’s working on it now, feeling it out, bit by tiny bit. He’s not daunted by the idea that he can’t see the whole story beforehand. “I don’t think you need to. It’s sort of like walking in the fog, or a blind donkey on the Grand Canyon trail, or in West Virginia on a highway — you just have to see be able to the next curve in the road, which is not very far.”

He’ll work on that novel with the help of a few writer friends, the ones who show up to the writers group meetings, the ones he attends 2–3 times a week. These here. That’s him in the photos.

Makes you think he might be on to something.

Paul lives in the Coronado District of downtown Phoenix with his wife Keri and their two kids, Eleri and Harmony.

Photos by Robert Hoekman, Jr.